By Mark A. Sequeira

As the country grapples with the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the most severely impacted sectors has been higher education. To their credit, institutions of higher learning were generally ahead of K-12, businesses, and other organizations in their response to the virus. As schools sent students home, they scrambled to transition their traditional in-person instructional models to an online one. There have been numerous articles detailing the adverse economic impacts of this pandemic on America’s institutions of higher learning. As has been the case historically in this country, any crisis affecting the mainstream is compounded in its effect on America’s marginalized demographics, especially Black people. So, it is no surprise that our beloved HBCU’s are projected to be more severely impacted than the rest.

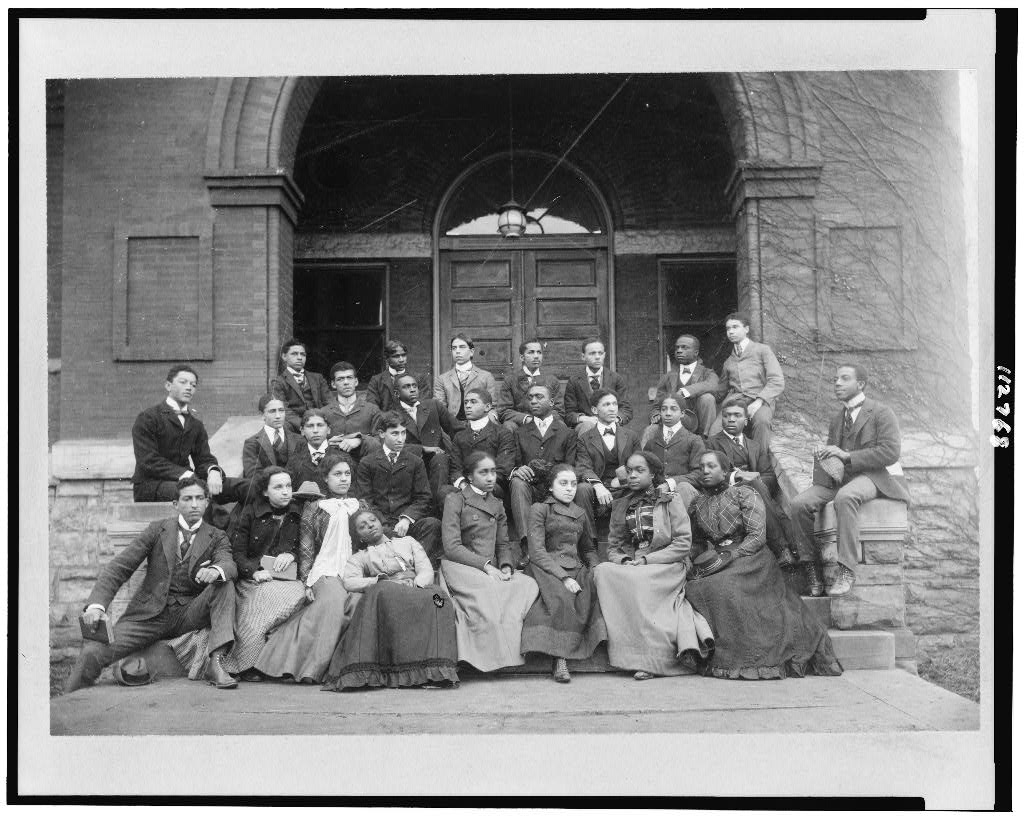

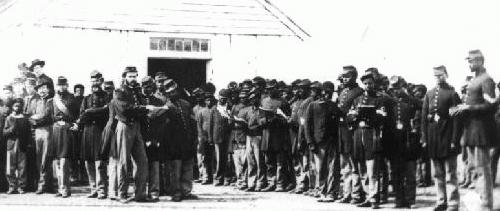

In assessing the state of HBCU’s, it is important to note that the COVID-19 pandemic is not the cause of HBCU financial distress, but is merely an accelerant. HBCU’s have operated in crisis for nearly their entire 183 year existence, persevering in the face of intentional underfunding, political and legal malice, and state-sanctioned violence. In absolute numbers, college enrollment overall has declined 8% from 2010 to 2018. This decline is significantly more pronounced considering the U.S. population increased during that same time period. The enrollment issue is an additional encumbrance heaped upon the longstanding burdens afflicting HBCU’s, the accumulation of which threaten the very existence of all HBCU’s, bar none. Despite the notion of some, there is not a single HBCU whose financial standing is robust enough to render them exempt from closing their doors forever. There are more than 50 individual colleges/universities with endowments higher than the sum total of all HBCU endowments combined. Given the gravity of the situation, what must we do to ensure the survival of our illustrious institutions?

I. Reimagine the Educational Model

Trades as Currency

In a nutshell, the traditional college/university model is unsustainable. From 2007 to 2017, the inflation-adjusted cost for college rose 34% at public institutions, and 24% for private institutions. In contrast, inflation-adjusted median incomes rose only 2.5% over the same timeframe. It should be emphasized that this increase in cost does not only affect the lower-income strata of the population. An increasing proportion of middle class and upper-middle class demographics are unable to independently cover the costs of their children’s education. At the rate college costs are outpacing earnings, eventually only the wealthiest of the population will be able to afford college. Since only 10% of American families have household incomes greater than $200,000, there simply will not be enough financially eligible students available to support the 4,200 degree-granting institutions in the United States. Most will have to close their doors. The only way to avoid this is to reduce the cost of education. HBCU’s are particularly impacted because they have a disproportionately high number of students from financially disadvantaged circumstances.

One possible solution is to incorporate trades such as plumbing and Information Technology into the educational curriculum. While some may scoff at the notion, it should be noted that this has been done many times in the past, at HBCU’s as well as other institutions. All land grant institutions established by the Morril Act of 1862 (Second Morril Act of 1890 for HBCU’s) mandated that the schools provide instruction in the “agricultural and mechanic arts”. While those “arts” eventually became standalone science and engineering curricula, they were initially considered trades. In fact, there was even opposition to including such trades in the classical higher education curricula of the times. Many HBCU’s leveraged the funding from the Second Morril Act to keep their doors open. In short, all land grant HBCU’s initially included trades in their curriculum. Many private institutions did as well, although there was no Federal funding incentive for them to do so. In Georgia, if you are a student pursuing “a career field identified as strategically important to the state’s economic growth”, then trade school is basically free via grants offered through the state. Eligible pathways included medical assisting, nursing, cybersecurity, welding, barbering, diagnostic medical sonography, and about 50 other fields. It is likely that many states offer similar grants for education in various trades. It would seem prudent for HBCU’s to take advantage of the available funding.

Revenue in Certifications

In nearly any industry, one recurring complaint is that recent college graduates are often ill-equipped to “hit the ground running”. While traditional and foundational coursework in a particular discipline is essential for the comprehensive training of students entering a certain field, such coursework is often inadequate for professions which require a steep learning curve for success. Even students have begun to understand this, as an increasing number of recent college graduates are adorning their resumes with additional training and certification that they have undergone in order to increase their attractiveness to employers. Companies like Coursera offer training and certification in Python programming, Artificial Intelligence, Data Analytics, Machine Learning, and 100’s of other relevant disciplines. Courses can range from 6 weeks to 6 months in length, depending on content and required hours per week. Some HBCU’s already offer such certifications, but all of the institutions should have these kinds of programs. Certifications yield additional revenue and need not be limited students. External students, professionals, organizations, and companies should comprise the bulk of the offerings, thus attracting revenue from sources external to the students and the schools.

Monetize the Expertise

HBCU’s are centers of creativity, diversity, intellect, and brilliance. Institutions ought to tap into these qualities by aggressively pursuing entrepreneurial endeavors. As a simple example, almost every school has a chemistry department with the faculty expertise necessary to create something as mundane as soap. Collaboration with the business and marketing departments of the school could yield a marketable product. Businesses like The Honeypot Company, a Black-owned company specializing in natural feminine care products, have demonstrated the efficacy of targeting underserved or underrepresented demographics. Certainly, an HBCU line of soaps and healthcare products would have a sizeable market of loyal customers. Similar endeavors could be explored in other areas. Computer science departments might attempt to monetize the creation of gaming apps. Psychology and education departments might administer professional services in therapy and counseling, even establishing revenue-generating clinics. The possibilities are endless.

II. Pool Resources

HBCU’s represent 107 diverse and glorious institutions, each unique in its offerings, expertise, and traditions. Collective survival will require collaborative efforts between all institutions. There ought to be routine HBCU meetings or conferences where administrators share best practices and brainstorm novel ideas to advance the institutions. It is important that these meetings not merely seek to replicate what notable PWI’s have done, as such solutions may not always be applicable to HBCU’s. Additionally, HBCU’s have a diversity of perspective that is lacking at most PWI’s, so HBCU’s have an opportunity to be pioneers in education and pedagogy.

In some ways, HBCU’s could operate as an academic mega cluster, where a student enrolled at one HBCU would have the luxury of spending a semester or year at any of the others, without any administrative obstacles. Such a program would foster solidarity among the schools and encourage synergy of ideas and experiences. The establishment and fortification of social and professional networks would be an added benefit.

There is also a funding element that could be explored. Consider establishing an HBCU Fund where all schools are contributing participants. On Giving Tuesday, there were HBCU’s that managed to raise almost $1 million in a day. Suppose the fund set an initial goal of $1 million in a year, which should be feasible for every school. Over 100 schools hitting the goal would represent more than $100 million. In 10 years that would be $1 billion, assuming nothing was done with the money. If the target $1 million were adjusted upward based on a conservative 1.5% inflation every year, the 10-year total would increase by $114 million. Of course, prudent investment would yield more. Harvard typically earns about 8.5% net annualized returns on its endowment. Morehouse, Spelman, and Howard yield similar returns. If those returns were applied to the proposed HBCU fund, then the 10-year total would be $1.7 billion. The fund would operate independent of the schools’ administrations, but for their benefit, at the discretion of the fund. Several items would certainly need to be worked out, but capability can undoubtedly be found among the brilliant alumni.

III. Synergy in Merging

HBCU’s represent a full spectrum of academic and cultural traditions that are cherished and passed down through generations. It is, however, becoming increasingly difficult for a single institution to survive and thrive in a competitive environment where institutional costs are outpacing household earnings. One way to combat this would be to leverage the resources and expertise of multiple HBCU’s via mergers. The mere mention of this strategy often incites immediate objection, even outrage. The two most common objections tend to be 1. We don’t want to lose our unique, cherished traditions and 2. There’s nothing in it for our institution. Sometimes it seems many would rather lose their institution than even consider merging with another. The first objection can be countered by noting that many HBCU’s have survived and thrived by doing this in the past. Clark College and Atlanta University merged to become Clark Atlanta University. Virginia Union is the result of the union of Wayland Seminary, Richmond Institute, Hartshorn Memorial College, and Storer College. The University of the District of Columbia and Harris-Stowe State are others. Additionally, there is no requirement that individual schools lose their identities in a merger. Again, there are many examples of schools accomplishing this. Oxford University maintains 39 colleges, which are self-governing, have their own admissions requirements, activities, and traditions. Barnard College for women is affiliated with Columbia University, but operates legally and financially separate from Columbia. Graduates of Barnard receive degrees from both Barnard and Columbia. Radcliffe College for women shares a similar history with Harvard. The Peabody College at Vanderbilt is another example among many. The counter to the second point may be a corollary to the first counter. What did Harvard stand to gain from absorbing Radcliffe? What was in it for Columbia when their board agreed to establish a separate college for women? There is no doubt that Columbia and Harvard benefitted from the diversity of intellect and perspective that women contributed. Similarly, certain HBCU’s would certainly benefit from the intellectual and cultural strengths that other HBCU’s offer. The sentiment that certain institutions have nothing to gain from others is a dangerous one that will potentially leave many institutions to fail, and those who promote their exemption will likely face a contrary reality. There is room for all to survive, maintaining their individual identities and creating new ones.

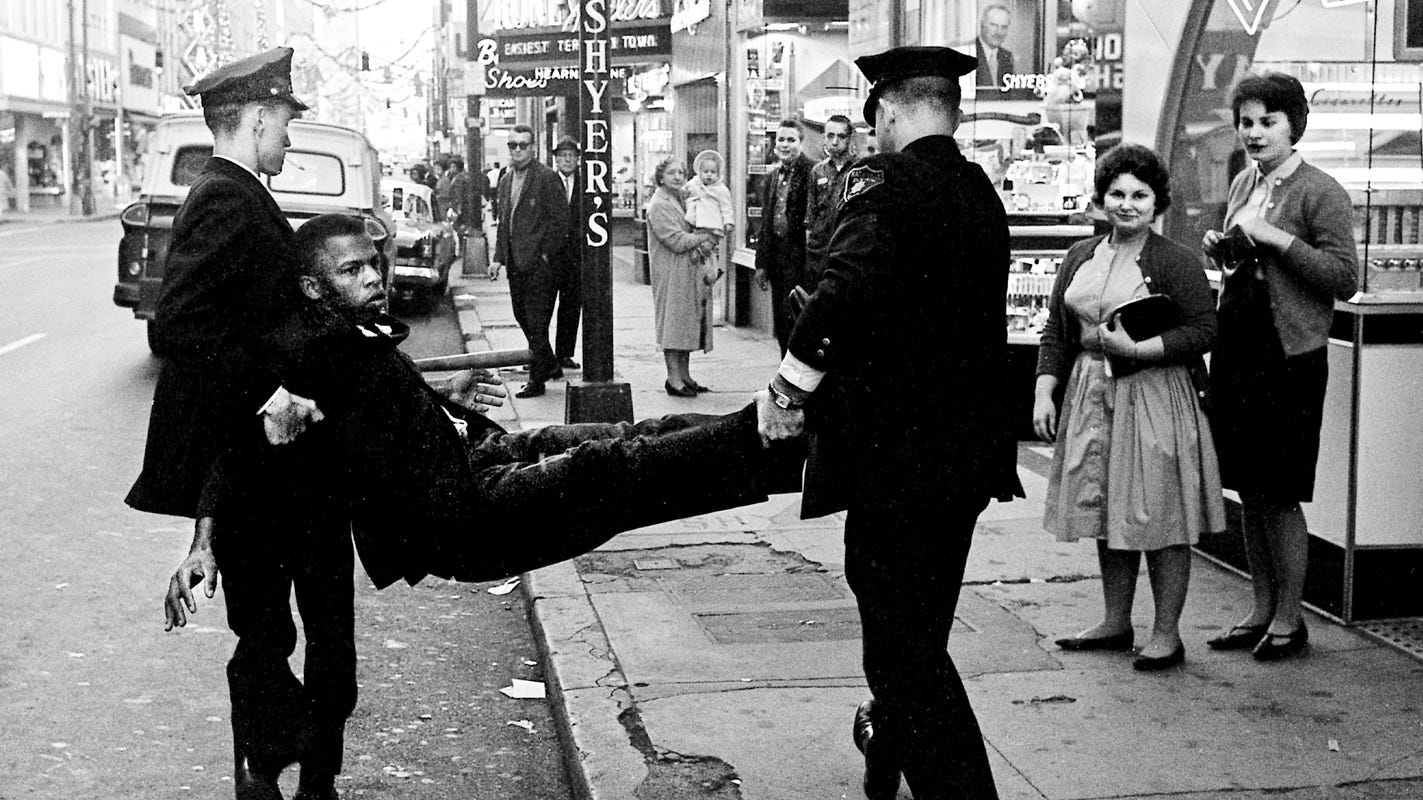

IV. File Suit

Throughout their entire existence, HBCU’s have operated under threat, physical and legal. Malicious fires destroyed the campus of Roger Williams University in Nashville, eventually forcing them to close their doors forever. Governor Elbert Carvel and the Delaware State Senate attempted to close Delaware State University, but the students, alumni, faculty, and administrators fought valiantly to prevent it. Local residents of Maryland filed a lawsuit to prevent the construction of Morgan State University, but eventually failed. The state of West Virginia weaponized the Brown v Board of Education decision to pull funding from Storer College and convert West Virginia State and Bluefield State to commuter colleges. States have also been guilty of intentionally underfunding HBCU’s while redirecting funds to their flagship state schools. The state of Pennsylvania awarded Cheyney State a paltry $35 million for intentionally underfunding the school. Mississippi awarded $503 million over 17 years to be split among Jackson State, Mississippi Valley State, and Alcorn State. University of Maryland Eastern Shores, Morgan State, Bowie State, and Coppin State will split $580 million over 10 years as a result of Maryland’s underfunding. While these victories aren’t inconsequential, the settlements still fail to comprehensively address the lost accumulation of wealth, revenue, enrollment, and research capabilities of HBCU’s. One judicious approach might involve HBCU’s collectively pooling resources and legal expertise to bring suit against respective states. The Maryland case took 13 years to settle, 19 years for Pennsylvania, and 26 years for Mississippi. The length and expense of these suits are likely correlated with the outcomes, but the full weight of 100+ institutions in every case might produce quite different results. There is more than enough expertise among alumni to execute on this front.

V. New Legacies

The aforementioned propositions are not meant to represent an exhaustive list of solutions, but rather some examples to motivate alumni and friends of HBCU’s to proactively create and implement solutions that will ensure the institutions not only continue to be relevant, but establish themselves as the premier model of success going forward. Meetings need to be had, alliances forged, plans made, strategies executed, and success measured. HBCU’s were forged out of adversity and crisis, and their contributions to America and the world are nothing short of miraculous, given the circumstances. We marvel at their perseverance and laud their resilience, but crisis cannot be the foundation of our future. In fact, it is increasingly evident that crisis, like the current pandemic, will eventually destroy us if we do not enact appropriate measures now. Let us use this moment to build a new foundation that allows us to operate from a place of strength. HBCU’s have a demonstrated track record of doing the impossible, so let us leverage that ability to reimagine our future and create an eternal legacy.